Local research group discovers a new way to shut down a pair of cancer-driving proteins, pontin and reptin, using the structure of an FDA-approved drug

Pontin and reptin are proteins that are involved in several cancer-driving mechanisms and play key roles in several diseases, including liver, colorectal, breast, lung and bladder cancers. This makes them a hot target for cancer drug development and discovery efforts. Currently, there is only one drug class that may hold some promise to shut down these proteins, but a Toronto-based team of scientists has recently broken new ground.

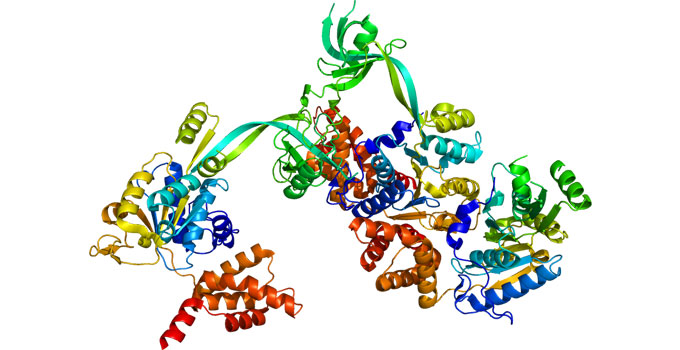

Dr. Walid Houry’s Lab at the University of Toronto and OICR’s Drug Discovery group have discovered that pontin and reptin, also known as RUVBL1 and RUVBL2, may be blocked to prevent cancer growth using a chemical similar to the FDA-approved drug, sorafenib. Their findings, which were recently published in Biomolecules, could be a starting point for new and improved cancer drugs based on the approved drug’s structure and function.

“Through our research, we detangled a large, complex process of interactions between proteins, but what we found was both rewarding and exciting,” says first author Dr. Nardin Nano, who was a PhD student in the Houry Lab while leading the study. “Our findings suggest a new target for cancer treatment and that a new therapy could be within reach.”

This study is part of a larger initiative, led by Nano and members of the Houry Lab, to further describe the function of these proteins in helping cancers grow and invade tissues. With their newfound understanding, the Houry Lab will continue to design and develop molecules similar to sorafenib that can better target pontin and reptin.

“I look forward to future studies that will use this knowledge to better inhibit these proteins in vivo,” says Nano. “Although there is more work to be done, I’m proud that this discovery can help guide future drug development efforts.”

“Given the multiple roles of pontin and reptin in carcinogenesis, it’s not surprising that they are promising drug targets,” says Houry, who is a Professor at the University of Toronto and supported by OICR’s Cancer Therapeutics Innovation Pipeline. “These findings motivate us to continue developing pontin and reptin inhibitors as potential anti-cancer compounds that could – one day – help a number of patients with the disease.”